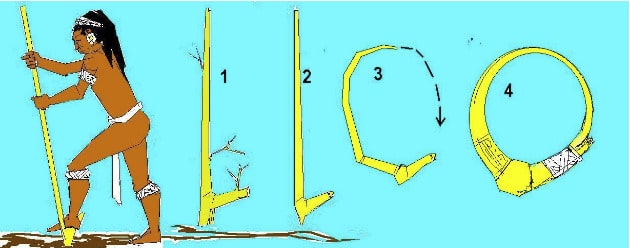

What is a Coa?

The use of digging sticks for the cultivation of the soil is a widespread custom among native peoples all over South America. There is evidence that many tribes who engaged in the agriculture of tuber roots such as the potato of the Andean Incas and the yuca of the Amazonian Arawaks utilized digging sticks with foot rests that allowed greater force to be applied to the tool via the use of the leg muscles.

We believe that the ancestors of the Taino used two kinds of digging sticks, one with a footrest and the other without. Today only the digging stick without the foot rest survives in the peasant farmlands of Cuba and still goes by the ancient Taino name of “coa”. However, modern Andean farmers still use the footrest type of digging stick in the highlands of Peru.

The archaeological author Eugenio Fernadez Mendez (Fernandez-Mendez 1972) maintained that the Tainos associated the Taino Mother spirit (whom he identified as Ata Bey and Gua ban Ce) with the image of the snake. He also maintained that the so-called “stone collars” were actually representations of the maternal snake spirit, an allegorical “serpent”’ as a result of the similarity in shape and form. The coa also was such a sacred serpent which allowed it to peek into the inner reaches of the Mother Spirit’s womb every time the Taino farmer pushed his or her foot down on the foot-rest and the coa was buried into the soil. The coa was used as a kind of messenger to the inner Earth Mother to plea to her on behalf of the farmer for good crops.The Tainos, no doubt, found a way to ritualize the long snake-like shape of the coa further by taking ceremonial, non-utilitarian wooden coas and soaking them until it was possible to start bending them. This action allowed the Tainos to make the shape of the agricultural instrument more “snake-like” by turning it into an image of a coiled serpent. The end of the long pole was then tied to the foot-rest to create the characteristic ovoid shape that is familiar to anyone who has seen the famous Antillean “stone collars”.

As they often did, the Tainos adapted this wooden image to their other favorite art medium, stone. Obviously the stone pieces are the ones that most easily survived the ravages of time and Spanish Inquisition destruction.

The ritual oval-shaped coa-hoop not only represents the coiled sacred serpent but also the pear-shaped outline of a human uterus. It is the image of Ata Bey’s all-creative womb and the reflection of the circle created by the 28-day menstrual cycle. It is the imagery that comes to mind when one thinks of the moon “Karaya” and its allegorical link between the human woman and the Divine woman.

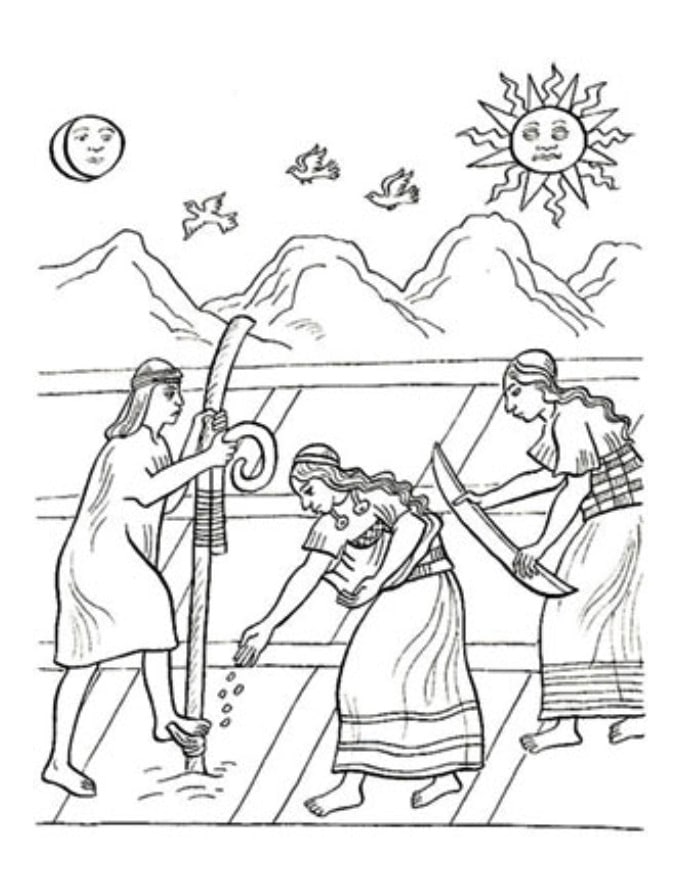

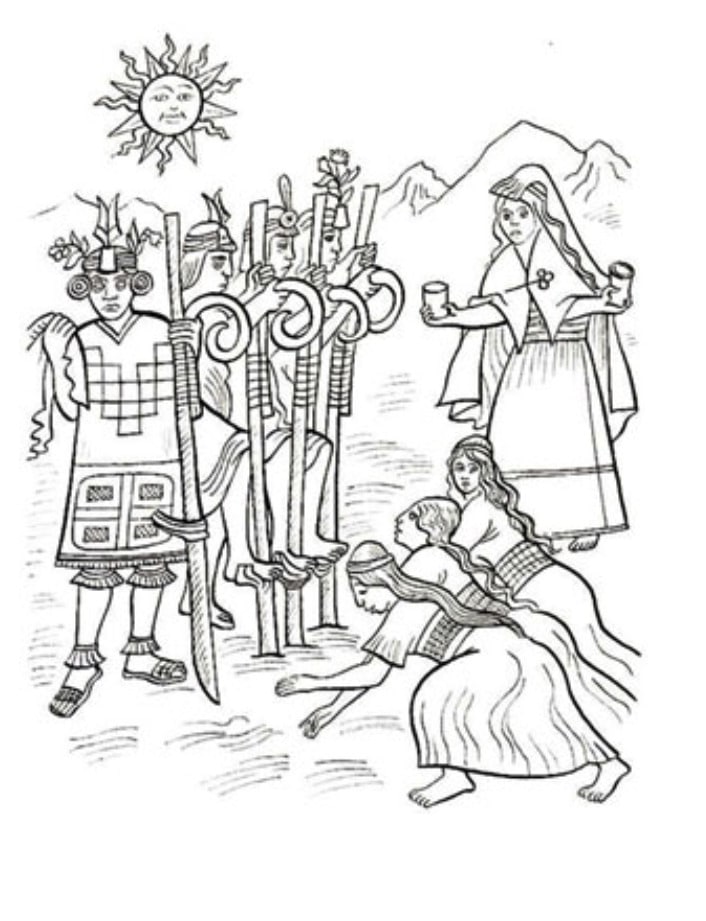

Drawings of Inca farmers using “foot-rest” type of digging sticks in the fields of ancient Peru.

Estos dibujos representan labradores Incas usando palos de siebra dotados del apendice para afincar con el pie.

El autor arqueológico Eugenio Fernandez Mendez (Fernandez Mendez 1972) supuso que los taínos asociaban al espíritu materno (quien él identifica con los nombres Ata Bey y Gua ban ce) con la imagen de la serpiente. También presenta la tesis de que los llamados collares líticos en realidad representan esa culebra espiritual en posición enroscada. Se puede postular que por su forma larga y angosta la coa pudo llegar a representar también esa culebra espiritual. Indudablemente el collar litico no es nada más que la representación en piedra de un objeto de madera que originalmente se formó al doblar una coa ablandada con agua para formar un ovoide o un óvalo amarrando las dos puntas del palo doblado. Después los taínos, quienes eran famosos por trasladar obras elaboradas de un medio a otro medio, empezaron a tallar esa misma imagen en piedra en vez de madera. Estos objetos de piedra sobrevivieron el tiempo más fácilmente que los de madera.

El uso de palos puntiagudos con los cuales se abren hoyos en la tierra para sembrar es una costumbre ampliamente difundida entre los pueblos indígenas de América del Sur. Hay evidencia que comprueba que muchas tribus que suelen cultivar tubérculos como las papas de los pueblos andinos y las yucas de los Araucanos amazónicos, utilizan estos instrumentos de agricultura. Algunos de estos palos están dotados de una clase de apéndice firme que sirve para acomodar el pie y con el afincar duro para más profundo poder hundir la punta en la tierra.

Creemos que nuestros antepasados Taínos usaban dos clases de palos de siembra, algunos con dicho apéndice y otros que carecen de él. En el día de hoy solo los que no lo tienen continúan en uso entre los guajiros de Cuba y se les llama “coa”. Pero en la cordillera de los Andes peruanos los campesinos todavía usan palos de siembra que tienen ese apéndice.